To

some, world history can seem a tricky

subject. For one, we have to consider

questions that are not even addressed in a common national history curriculum such

as “American History from 1776-1865.” Questions

such as the role of statehood, the rise and fall of state models, the

cultivation and manipulation of trade/exchange, as well as the nature of

history itself as a method (social science).

Georg Hegel described world history as a subject “not concerned with

general deductions drawn from history, illustrated by particular examples from

it—but with the nature of history itself.”[i] World history is much more than simply

depicting and interpreting external actions and events; it is a process of

reason, culminating into an over-arching theory for not just society, politics,

and economics—it is a process of the development of all ideas through reason. Few books

have I come across in recent years that have the quintessential essence of

Hegel’s historical logic than Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century, which is the focus of this

review.

This

review is part of a series of reviews I’m writing not only for others but also

for myself, to keep a log of some of the particular texts that have a large or

profound influence on the way I develop my understanding of history in general

as well as my specific field in world history—historical capitalism. This is the first review I’m actually posting

from this series, but is not necessarily the first review written on major

books that I’ve read. I am also engaging

in this project (so to speak) because

of an article in one of the more recent editions of the American Historical

Association’s Perspectives on History. The article, by Seth Denbo, emphasized that history as a subject was losing traction

as a “book discipline” due to “rapid changes” with both “engagement” as well as

“the communication of ideas” among scholars and their students.[ii] Overall, it is important for emerging

scholars and especially historians to consider the utility of the blog format

in order to not only maintain standards of writing and professionalism but also

to maintain flexibility and roots with dominant streams of communication and

student engagement.

Arrighi’s

subtitle to his early 1990s text is “Money, Power, and the Origins of Our

Times,” but the typical reader might be off put when they learn the real

meaning of Arrighi’s overall title; “The Long Twentieth Century.” Arrighi’s work stems from two schools of

thought primarily, a tradition following Braudel and Immanuel Wallerstein, and

a tradition following Joseph Schumpeter; all of whom examined what Wallerstein

described as “historical capitalism.”[iii]

Arrighi’s title comes from Braudel’s

notion of a longue durée, or a prolonged

period of historical development outside the strict confines of “centuries.” Braudel credited his concept to Karl Marx,

stating that it was ultimately his “true genius.”[iv] Because of this, Arrighi’s “Twentieth Century”

spans nearly 450 years, from the mid-16th century to the late 1980s,

and with good reason. Arrighi’s central

concern, made clear in his preface, is an attempt to examine the confusion and

bewilderment by social historians over the rapid development of a flexible

economic order with hegemonic control remaining in the West, and no possible

hint of an overall collapse:

“Over the last quarter of a century something fundamental

seems to have changed in the way in which capitalism works. In the 1970s, many spoke of crisis. In the 1980s, most spoke of restructuring and

reorganization. In the 1990s, we are no

longer sure that the crisis of the 1970s was really resolved and the view has

begun to spread that capitalist history might be at a decisive turning point.”[v]

On this premise, we are invited to understand the

development of capitalism from a big scale view—one where the immediate

instances of crises actually are found to have a pattern, rooted in the very

development of capitalism as a world-system.

Expanding onto the works of David Harvey and

other 20th century Marxist economists/social theorists, Arrighi

described the perceived rigidity of the Fordist-Keynesian period of the

1920s-1960s as an illusion: its rigidity

was one sway of a larger process between flexible and structural capital

investment. These fluctuations exist on

the larger, “long twentieth century” scale, and can be read “as a restatement

of Karl Marx’s general formula of capital: MCM’.” This is directly related with the

long-standing notion that Marx’s reduction of capitalism’s overall crisis,

the tendency for the rate of profit to fall (P), was proven false by the 1970s. Even recent publications such as Thomas

Picketty’s Capital in the 21st

Century alluded to such an idea because of the fact that “after the

initial boom of mechanization, the most advanced kind of capitalism reverted to

eclecticism—to an indivisibility of interests.”[vi] Referencing the bounce-back of capital gains

during the 1980s, the seemingly flexible nature of world capitalism appeared to defy the long-standing

perception of an overall crisis. In other words, it appeared that capitalism was adaptive as opposed to rigidly fixed. Utilizing a longer time scale, however, Arrighi suggested that Marx’s formula for capital contained the explanation of capitalism' flexibility long

before Marx even addressed P, two volumes later in Das Kapital:

“Marx’s formula tells us that capitalist agencies do not

invest money in particular input-output combinations, with all the attendant

loss of flexibility and freedom of choice, as an end in itself. Rather, they do so as a means towards the end of securing an even greater flexibility and

freedom of choice at some future point.

Marx’s formula also tells us that if there is no expectation on the part

of capitalist agencies that their freedom of choice will increase, or if this

expectation is systematically unfulfilled, capital tends to revert to more flexible forms of investment.”[vii]

In other words, we can understand the flexible nature of

capitalism as a system if we simply accept that P (the tendency for the rate of

profit to fall) explains the cause of

this flexibility, as opposed to being the reason

for its rigidity and supposed-necessary crisis.

Capitalist agencies “prefer liquidity,” but need periods of rigidity to

maximize the potential flexibility at

some future point.

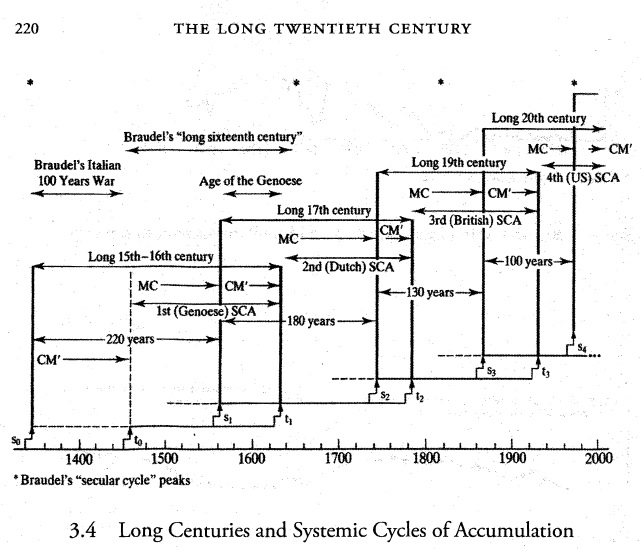

Arrighi

uses the oscillating phases of Marx’s MCM’ formula throughout the text to

continue to explain the development of “material expansion” versus “financial

expansion.” Material expansion finds its

highest levels of success in (MC) phases of production, where “the capitalist

world economy grows along a single developmental path,” while financial

expansion sees success only after “the established path has attained or is

attaining its limits, and the capitalist world economy shifts through radical

restructurings and reorganization onto another path.”[viii] It is precisely these “radical restructurings

and reorganization” that direct Arrighi towards his sense of historical

agency. Examining the three major

hegemonies of historical capitalism, Arrighi draws on the dynamic shifts—both internal

and external—to the capitalist world system under, first, the Italian

City-States during the Renaissance, second, the rise of Dutch trading and its

supremacy under the English/British, and third, the global hegemonic order

established by the United States.

Mixed

into the shifts of capital investment during this time, however, Arrighi does

take the time to address periods of state-formation which highlight the various

regime orders that existed throughout capitalism as a world-system. In doing so, he makes some very powerful

observations and arguments by building off the works of Wallerstein and Janet

Abu Lughod. By discussing the

development of capital alongside state-formation, Arrighi coaxes the reader

into the notion that the two are directly linked; a prime example being his

explanation of why Europeans discovered America:

“It follows that the expected benefits for Portugal and other

European states of discovering and controlling a direct route to the East were

incomparably greater than the expected benefits of discovering and controlling

a direct route to the West were for the Chinese state. Christopher Columbus stumbled on the

Americans because he and his Castilian sponsors had treasure to receive in the

East. Cheng Ho was not so lucky because

there was no treasure to retrieve in the West.”[ix]

Following Arrighi’s logic to its natural conclusion, the “West

was won” by simply a matter of beneficial economics working through the powers

and accumulated wealth of states. It

should not be considered, however,

that Arrighi is suggesting that agencies of capital and agencies of statehood

operate on the same motives, nor that states themselves always operate on the

same developmental path. In fact,

Arrighi splits the motives for power into two categories.

“Capitalism,”

for Arrighi, represents the first and primary strategy for state-formation and “logic

of power.” It is contrasted with “territorialism,”

which seeks “control over territory and population.” The "territorialist" logic of power utilizes mobile

capital and the flexibility of exchange as a means to an end: “mobile capital

[is] the means of state- and war-making.”

For the "capitalist" logic of power, “the relationship between ends and means

is turned upside down….and control over territory and population” become the

means for advancing capital return.[x] This not only explains the aforementioned

example of how the West was “won,” but also the variances of state formations

throughout the world-system in all its regions; the Core, the Semi-Periphery,

and the Periphery (Third World).

Arrighi

concludes his text by reminding readers of the persistent crises in capitalism as

illustrated by former great thinkers.

Rather than perceive "crisis" as a single, history-defining event, Arrighi poses to us

the suggestion that crises are not only a recurring tendency of capitalism, but also serve as

a self-balancing mechanism which allow flexibility of investment, which then

sustain capitalism by handicapping

it. In other words, Schumpeter’s 1941

suggestion that capitalism might survive another prolonged run of development

has “been proven right; but the chances are that over the next half century or

so, history will also prove right his contention that every successful run

creates conditions under which it becomes more and more difficult for

capitalism to survive.”[xi] This further highlights a powerful argument

against perceptions of an unfettered, anarchistic capitalism:

“Such an institution could not exist for any length of time

without annihilating the human and natural substance of society; it would have

physically destroyed man and transformed his surroundings into wilderness. Inevitably, society took measures to protect

itself, but whatever measures it took impaired the self-regulation of the

market, disorganized industrial and agricultural life, and thus endangered

society in yet another way. It was this

dilemma which forced the development of the market system into a definite

groove and finally disrupted the social organization based upon it.”

Tracing the development of historical

capitalism across three hegemonic epochs and examining the world-system from

the top down (that is, from the Core to the Periphery), Arrighi sets a gold

standard for examining world history that could effectively replace the

traditional Western Civilizational

approach. For too long history has been

a narrative of nation versus nation, people versus people. Arrighi’s text challenges that perception by

examining social order versus social order, and class versus class. Nations, statehood, and people are the

agencies by which social orders and classes act, or cause, history. Hegel would

certainly appreciate Arrighi’s contribution here, as it breaches further away

from the “original history” of Herodotus and Livy, the “reflective history” of

Braudel and Wallerstein, and instead embodies “philosophical history;” or—to paraphrase

Hegel—a strand of history that is both conscious of itself and conscious of its

effect on social ideas.

[i]

Hegel. “The Three Methods of Writing

History,” in Reason in History: A General

Introduction to the Philosophy of History (New York: Bobbs-Merrill Inc,

1953), 3

[ii]

Denbo, Seth. “History as a Book

Discipline” in Perspectives on History,

Vol. 53, No. 4 (April 2015), 19

[iii] See: Wallerstein, Immanuel. Historical

Capitalism (New York: Verso, 1983)

[iv] Braudel,

“History and the Social Sciences” in On

History, p. 50-51

[v]

Arrighi, Giovanni. The Long Twentieth Century (New York: Verso, 1993), 1

[vi]

Braudel. The Long Seventieth Century, quoted in Arrighi, 5

[vii]

Arrighi, 5

[viii]

Ibid, 9

[ix]

Ibid, 35

[x]

Ibid, 34-36

[xi]

Ibid, 325

No comments:

Post a Comment